|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| ||||

|

| |||||||

|

|

Research is the foundation upon which the Meinwald Group is built. As past, ongoing, and future projects are adapted to web format, they will join the ranks of the research represented on these pages.

Chemical Defense of the Cabbage Fly: the MayolenesThe European Cabbage butterfly, Pieris rapae, is a widely distributed insect. A native to Eurasia and North Africa, it was accidentally introduced into Canada about 1860, from where it spread over most of North America. It also has become established in Bermuda, Australia, Hawaii, and other Pacific Islands (1). As a larva it prefers plants of the crucifer and caper families (Brassicaeae, Capparidaceae), and it is a common pest on cabbage, Brussel sprouts, and cauliflower (1).

Adult Pieris sitting on a flower, and Pieris larvae (red arrow) feeding on cabbage. Pursuant to a study of the defenses of a number of larval insects, we noted the caterpillars of P. rapae to be beset with glandular hairs, such as pierid larvae had been reported to possess (2) but had never been investigated. In P. rapae these hairs are arranged in rows along the full length of the body and they occur in all larval instars. Their product is a clear oily fluid that collects as droplets at the tip of the hairs.

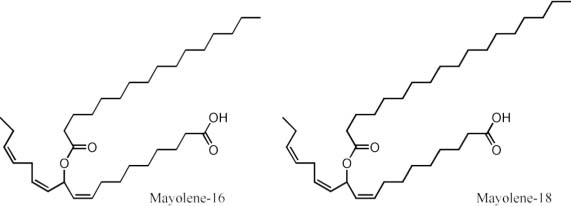

A Pieris larva. On the assumption that this secretion might be protective and responsible in part for P. rapae's extraordinary adaptive fitness, we looked into both the repellency and chemistry of the fluid. We found the secretion to be potently deterrent to ants, and to consist primarily of a series of unsaturated lipids, which we named the mayolenes.

It seems established that the secretion of the glandular hairs of larval P. rapae is defensive and that its principal components are the mayolenes. The secretion could clearly be effective against arthropods other than ants, including such enemies as wasps, bugs, beetles, spiders, harvestmen, and parasitoids. Glandular hairs are a common defensive feature of plants (4), where they have been shown to be effectively protective against insects (5). They are of less frequent occurrence in insects, but the chemistry of the secretion of insectan hairs, to the extent that it is known, can be of interest. Thus, for instance, the pupal hairs of certain coccinellid beetles have been shown to produce, in one species, a series of novel alkaloids (the azamacrolides), and in two others a combinatorial mixture of macrocyclic polyamines (6-8). The present discovery of yet another novel novel group of secondary products from the glandular hairs of an insect suggests that the study of such defensive materials can pay off. |